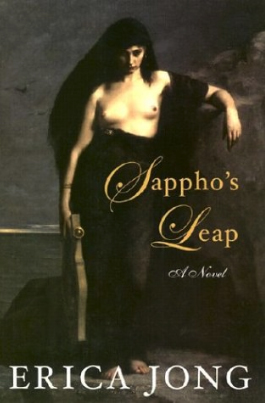

Sappho's Leap

If you could go back in time 2600 years and get inside the head of the greatest singer of love the world has ever known, Sappho's Leap would be the result. An odyssey of love and adventure which spans the ancient world, Erica Jong's witty, sensuous and compellingly readable new novel, tells the story of a passionate woman who was ahead of her time and whose songs have proven to be immortal. Jong's Sappho is a sort of female Odysseus, stretching the boundaries of time and space, journeying not only into the reality of the ancient world but also into lands of myth and legend which have shaped the way we imagine our lives today.

Born on the island of Lesbos circa 600 BCE, Sappho falls madly in love with the dashing poet Alcaeus, plots with him to overthrow the dictator of her island, is caught and exiled and married off to a repellent older man in the hopes that matrimony will keep her out of trouble. It does no such thing, instead it starts her off on a series of amorous adventures with both women and men which take her from Syracuse to Delphi to Egypt and even to the Land of the Amazons and the shadowy realm of Hades.

Fearless, heroic, yet full of vulnerability, Erica Jong's Sappho is one of her most unforgettable and exuberant heroines.

Reviews:

"Thirty years ago, Jong hot-wired American fiction with her galvanizing first novel, Fear of Flying, and she’s been writing with great moxie about women, sexuality, love, and misogyny ever since. Along the way, she has developed a unique style of historical fiction that combines precisely rendered settings with archly humorous social critiques and exuberant sensuality, a mode perfectly suited for this highly imaginative, sexy, and shrewd interpretation of the life of the first know woman poet, Sappho, who lived on the island of Lesbos 2,600 years ago and wrote and performed poems of indelible candor and eroticism. Jong envisions Sappho as an ardent and adventurous soul who, while still in her teens, meets the love of her life (the rebel poet Alcaeus), reveals her poetic talents, and is forced into exile and marriage to a wealthy old drunk. After being widowed and loosing custody of her beloved daughter, Sappho, despondent but ever valiant and resourceful, embarks on an elaborate odyssey a la Homer, accompanied by her female slave and lover, Praxinoa, and steadfast admirer and friend Aesop, of fable fame. Sappho survives shipwrecks, sorceresses, crooks, and tyrants, and visits the lands of the Amazons and the Centaurs, the oracle at Delphi, and the underworld, all under the avid eyes of Aphrodite, who insists that "a woman singer can be as great as any man," and Zeus who rejoins, "but I bet she throws it all away for the love of an unworthy man." As Sappho loves women and men alike, and saves lives with her poetry and quick thinking, Jong offers sly commentary on everything from slavery to superstition, greed, lust, vanity, deceit, age, and artistic freedom in a tale that is at once enormously entertaining and wisely provocative." —Donna Seaman, Booklist Review

"The feminist maverick who's been tweaking sexual conventions ever since Fear of Flying (1973) now reimagines the life and numerous loves of the seventh-century (b.c.) Greek poetess.

Sappho herself narrates, in another deconstructive romp akin to Fanny (1980) and Serenissima (1987), at the moment when she's standing on a seaside cliff about to "leap" to her death. Her story begins on the island of Lesbos, where she grows up a devotee of the goddess Aphrodite, who grants Sappho "gifts of immortal song." She falls in love with the handsome singer Alcaeus, who fathers her daughter Cleis (even though he prefers boys), and colludes with her in opposing the tyrant Pittacus, which sends her into exile. This allows Jong to parade her (quite impressive) research into classical culture and legend, as the politically and increasingly sexually conflicted adventuress undertakes an odyssey at least as arduous as Odysseus's. As Aphrodite and her randy father Zeus look down from Mount Olympus and comment on Sappho's peregrinations, she endures arranged marriage to the moribund merchant Cerclas, then sails about the known and unknown worlds, consulting the Oracle of Delphi, matching wits in Egypt with the notorious courtesan Rhodopis (who's extorting their family's fortune from Sappho's lovestruck brothers), and accompanied by the taciturn slave- abulist Aesop detours among the Amazons (whose queen commands the noted singer to compose a celebratory Amazoniad), the Islands of the Philosophers and Centaurs, respectively, even the Land of the Dead. Eventually reunited with Cleis, Sappho settles into celebrity status and middle age, until a virile young ferryman rekindles the familiar flames. Much of this is highly entertaining, and the sexuberantly anachronistic one-liners are sometimes wonderful ("Unless they [men] are castrated, their brains do not function properly"), sometimes effulgently absurd ("My longing for Cleis became the worm in the golden apple of our love"). But it does go on.

Nevertheless: one of Jong's most enjoyable books." —Kirkus Reviews

"In this beautifully written and thoroughly researched work of historical fiction, Jong attempts to rescue Sappho from the classical tradition that characterizes her as a sexual or social deviant as well as a victim of unrequited heterosexual love." —Robert Ball, Columbia University magazine, Fall 2003 edition

***"Jong's historical novel reimagines the extraordinary life of the legendary Greek poet." —Harper's Bazaar, May 2003

***In Print: Zipless No More

"Sappho was the first great bisexual," says Erica Jong. "She wrote about feelings that seemed very modern to me and that I could identify with." In Sappho's Leap (Norton; $24.95), the author who popularized the "zipless fuck" via her 1973 novel Fear of Flying fictionalizes the life of that ancient Greek icon of liberation. Around 600 B.C., the poetess (whose work and life are known only through the tiniest of fragments) recalls her Odyssean travels while contemplating her legendary and (and possibly apocryphal) suicidal cliff-dive. Naturally, she's learned lots of lessons — among them that limitless sex has its downside. "I don't think the zipless fuck is anything but a fantasy," says Jong now 61. "I never thought of it as a prescription. And I think it's interesting to write about women in maturity, as them begin to understand the consequences of their actions." Jong, who puts much of her life straight into her books, can draw a few parallels. "The experience of being someone who lives by words, and someone who lives for her daughter — those things come out of my life," she says. (Sappho and her daughter actually spend most of the book estranged, but reconcile towards the end; in that vein, Jong and her daughter, the memoirist Molly Jong-Fast, will discuss a few of their on issues at the Museum of Jewish Heritage May 11.) Jong, for her part, has survived the trials of popularity. "To be typecast as a kind of sexual heroine is a strange thing," she says. "But nobody gets exactly the understanding they deserve. We're all misunderstood, and I think true wisdom is accepting that. I'm more philosophical that I ever was. I'm grown up." —New York Magazine, May 12-19, 2003

***

A Tale of Two Poets New York — The most widely known anecdote about the poet Sappho concerns her death: She is said to have bethrown herself off a cliff because of unrequited love for the hunky boatman Phaon. Erica Jong, whose new novel is "Sappho's Leap" (W.W. Norton & Co.), contends that this story is nothing more than the fabrication of jealous male writers who wanted to undermine their rival's credibility. There were, after all, many satires that caricatures Sappho after her death.

Jong maintains that there is no them or metaphor in lyric poetry -- or for that matter, song — that was not created first by Sappho. She is justly celebrated for such lines as "I have a daughter like a golden flower" and "a subtle fire runs under my skin." "Every poet of consequence from Catullus to Sylvia Plath has rediscovered and reinterpreted Sappho," Jong says, "and all these years, she has never got the credit for it." In short, Jong contends that Sappho is the mother of all poets.

It seems appropriate that Jong would take on the calumny that has attached itself to Sappho's reputation, since she began her career as a poet and has published six books of poetry in addition to her eight novels. Then, too, she's known for giving voice to unheard women's thoughts, as in her famous bestseller, "Fear of Flying," which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. "A lot of my books are an attempt to find women's histories that are the histories of women rewritten by men," Jong says. Sappho, who was Greed lived 2,600 years ago, 200 years after Homer and a short while after Plato. But unlike those writers, most of what remains of her poetry is fragments. Some of the latter, Jong reveals, were actually so little regarded that he papyrus they were written on was used to wrap mummies, and the poems were only preserved and discovered by chance.

In addition to her new book and the anniversary of "Fear of Flying," Jong is working on another task, this one long-running — turning her 1980 novel "Fanny" into a musical. Her top choice for the lead, which she once summed up by asking "What if Tom Jones were a woman?" she notes, is Bernadette Peters because, "I've been following her for years. She has a wonderful voice and her renditions of songs are not like anybody else's. "Fanny" has been optioned by the Manhattan Theater Club.

At 61, Jong is still blonde, attractive and youthful-looking. She lives in a big, stylishly furnished apartment on the Upper East Side and in Weston, Conn., with her fourth husband, Kenneth David Burrows, who's a lawyer with a black standard poodle, Belinda Barkowitz. When she published "Fear of Flying," Jong says, she was a poet and medieval scholar in a Ph.D. program at Columbia. The book was a cataclysm, she recalls: "I went from being obscure to being the kind of person other people call in the middle of the night." She actually spent a year replying to readers who had written her about the book and their personal experiences; it wasn't until later that she realized that she didn't owe them anything and didn't have the time to do that.

As a writer, she says, her primary motivation is to get the reader to "turn the page." Her next project will concern aging, the way in which women in particular find that they are devalued as they get older.

These days, however, the women who helped liberate so many others from sexual conservatism, says that "the door opened in the Sixties and Seventies to sexual freedom hasn't fulfilled its promise. Younger people today, if they're not totally self-destructive feel that they want to settle down with partners." Her own daughter, Molly Jong-Fast, daughter of Jong and her third husband Jonathan Fast, who is also a writer, has never read her mother's books because she doesn't' want her writing to be influenced by them. Jong-Fast who wrote "Normal Girl," is engaged and is writing a series for Modern Bride about her upcoming wedding. —Lorna Koski, Women's Wear Daily

***

Cliff Notes

In Erica Jong's novel, Sappho's life flashes before her as she stands on a precipice.

Most gentlemen don't like love, the Cole Porter tune goes: ''As madam Sappho in some sonnet said, / A slap and a tickle / Is all that the fickle / Male / Ever has in his head.''

Creative, influential women have always attracted more hostility than praise. The most famous of a tiny handful of women in Western antiquity whose writings have survived, the Greek poet Sappho has been imagined through 26 centuries in shapes that reflect the anxieties of their time and place. Ancient readers considered her a composer of exceptional power, a mortal Muse whose image they memorialized in monuments and coins. But they also turned her near uniqueness as a female writer into a morality tale of sexual and social deviance.

On the basis of virtually no evidence outside her own artful poems, Athenian playwrights used Sappho as a character in their racy comedies. A few centuries later, Roman literary critics speculated that she was a prostitute — the only plausible career, they thought, for a woman who wrote so perceptively about erotic desire. The mold for modern equations of female creativity with psychological abnormality — the Emily Dickinson or Sylvia Plath stereotype — is Ovid's portrayal of Sappho as a desolate melancholiac. And reading those famous love poems, expressing passion for both women and men, all the ancients wondered: whom did Sappho really love, and in what way exactly? The Sappho produced by this tradition comes in two versions: an accomplished seducer of beautiful young girls and a victim of heterosexual heartbreak who killed herself for love of a man.

The Sappho that Erica Jong offers up in her historical fantasy ''Sappho's Leap'' is as hooked on slaps and tickles as Cole Porter's archetypal male. And Jong's fans wouldn't have it any other way. The author of the sexual-revolution classic ''Fear of Flying'' (1973) has a reputation to uphold, and she rises to the occasion by imagining Sappho as an updated compilation of every Jongian heroine to date. Despite the careful details describing the culture of the Greek islands in the sixth century B.C., this Sappho is a comfortably bisexual poet of the 21st century. Think swoons and sun-kissed skin, ripe flesh, ecstasy and anguish, and you're halfway to catching the drift of the novel.

But only halfway. True, the first dozen chapters parade the characters through a soapy plot filled with unintentional hilarities, where Sappho flounces and flirts like Scarlett O'Hara (''You little minx,'' her lover says, ''you want to devour the world'') and makes love like a Harlequin heroine (''His arms enfolded me. His heart thundered against mine. . . . Time vanished. Space collapsed''). In her afterword, Jong testifies that she wrote the novel to correct centuries' worth of fictions about Sappho she finds mocking and unfair. This is a good cause, if a novel needs one; it's gratifying to encounter a Sappho whose sex drive is based in pleasure instead of neurosis, and who is interested in politics as well as pillow talk. (In fact, the total number of her lovers is small, but the relationships are complicated by modern ''commitment issues'' that occupy a quantity of pages.)

The problem with framing the novel as an intervention into history is that it depends in part on making the fictional Sappho a plausible creator of the historical Sappho's poetry. Jong's own adaptations, interpolated through the book, show the poems' range: graceful calibrations of raw passion and allusive indirection, elegant turns of phrase capping bawdy banter. The utter lack of intuition that distinguishes Jong's young Sappho makes her authorship of this material simply impossible to believe.

Things take a turn for the better when the newly widowed poet travels to Egypt and beyond in search of her lost daughter, Cleis, and her exiled lover, the poet Alcaeus (whose poetry survives, like Sappho's, in fragments recorded by ancient scholars or scrawled on scraps of papyrus). Weaving the ancient pseudo-biographical oddments together in all their glorious incoherence, and adding a few of her own, Jong invents a Sapphic odyssey through the Hebrew Scriptures, Greek history, philosophy and myth. As she steers the novel into the realm of the fantastical, creativity and light humor help redeem the thin characterizations. The mature Sappho, happily, knows irony.

Sappho plays the role of Joseph when she rescues her brothers in Egypt (though, unlike Joseph in the story of Potiphar's wife, she revels in an affair with the lusty Pharaoh). The fable teller Aesop advises Sappho how to deal with her brothers' nemesis, the prostitute Rhodopis — an amusing story, but one that showcases Jong's irritating habit of setting up strong women as Sappho's bitterest antagonists. She sees the Sirens and the Harpies (more female monsters), corrects Homer's account of the underworld and reminds a group of Platonic philosophers of Aphrodite's delights. It's as though a women's writing group took ''Clash of the Titans'' as its theme of the week.

In one of the longest tales, recalling the camp appeal of ''Xena: Warrior Princess,'' Sappho and Aesop discover a separatist commune of Amazons. Their day-care system rivals Sweden's, but their literary taste is less progressive: they capture Sappho and demand that she write an epic ''Amazoniad.'' It is a huge success -- after the protofeminist Amazons dutifully censor the spicy parts. The queen faces a rebellion from a group of second-wave subjects, who protest old-fashioned separatism in favor of a sex-friendly new order. Will Sappho rule over them instead? the Amazons inquire. Sappho is intrigued at the prospect, but her answer is no: ''I loved the adulation and applause, but administration bored me.'' She leaves, after releasing Aesop from a cave, where he has been forced to spend days impregnating amorous Amazon virgins.

With Aesop's help, Sappho founds a utopia using a Ten Commandments of sorts, in an amusing parody of the biblical account. But her quest is not over. Like Odysseus, Sappho must return home to deal with political and domestic tensions. The novel melts back into melodrama through a series of midlife crises, from Sappho's reconciliation with Alcaeus and her mother and daughter to her rediscovery of passion, first with her music students and then with Phaon, an enticing younger man. In the ancient tradition, Phaon is the cause of Sappho's suicidal leap from a sea cliff. The novel opened with her steps toward the edge; it reveals Sappho's fate in the last chapter.

Erica Jong's celebrity will never rest on her literary talents. This is a book, after all, in which a friendly centaur can revive a languishing maiden with an ''arc of fire'' from its ''enormous'' phallus. But her effort to bring to life an ancient writer engrossed in politics, family and the creation of poetry is a relief from the relentlessly everyday sincerity of much current ''women-oriented'' writing. If only she had confronted the real historical mystery of how Sappho made her way in the violent, male-dominated world of ancient Greece — such a novel would have done justice to the remarkable woman that Sappho obviously was.

Joy Connolly teaches classics and political theory at Stanford University. —Joy Connolly, New York Times

Sappho's Leap